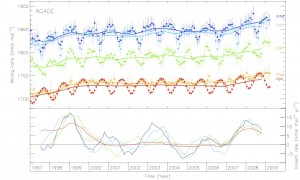

Methane is a strong greenhouse gas, and plays an important role in the chemistry of the atmosphere. Global concentrations are currently more than double their pre-industrial values (as shown by ice core data). However, in recent years this dramatic growth has slowed, and was close to zero between 1999 and 2006 (see graph below).

In this paper, published in Geophysical Research Letters, we presented AGAGE and CSIRO data showing renewed global growth of methane concentrations starting in 2007. We speculated that some natural process was most likely responsible for such a rapid change in concentration, since anthropogenic emissions tend to change more slowly (a few percent per year). For example, wetlands, the single largest source of methane, could have increased their emission rates in response to changes in temperature and precipitation (2007 was an extremely warm year over Siberian wetlands). Alternatively, we note that a modest decrease in the concentration of the chemical that destroys methane, the hydroxyl radical (OH), could produce a sudden growth.

There was an additional puzzle to this methane increase, which was that growth occurred across the globe at almost the same rate. Most of the methane sources are in the Northern hemisphere, so we would usually expect to see growth beginning in the North, and then propagating to the South later on. This near-simultaneous rise in concentration in both hemispheres suggested that tropical emissions could have played an important role.

In the two years since the publication of this paper, lots of groups have examined these strange fluctuations in methane levels. In particular, Ed Dlugokencky at NOAA and Philippe Bousquet at LSCE in France have written some very nice papers on the subject (Dlugokencky et al, 2009 in Geophysical Research letters and Bousquet et al, 2010 in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics Discussions). They find that the most likely explanation for the rise since 2007 has been an increase in emissions from northern wetlands in 2007 and then an increase in tropical wetland emissions in 2007-2008. They find little evidence for a large change in OH concentration or large increases in biomass burning.

Our paper received some press attention in 2008 (e.g. MIT press release, “Climate Warming methane levels rose fast in 2007”, Reuters). It was also quoted in several articles suggesting that melting arctic permafrost could be driving the increase (e.g. “A sleeping giant?”, Nature Reports Climate Change). How much the arctic permafrost melt is contributing to changing methane concentrations is still the subject of much research. However, as mentioned above, it seems most likely that the recent increases can be explained by changes in output from existing wetlands.

In addition to these articles, the paper also caught the attention of some people who drew slightly unusual conclusions from the work. Some thought we had “inadvertently disproved global warming” (“MIT Scientists Baffled by Global Warming Theory, Contradicts Scientific Data”, TG Daily). The article also triggered an interesting discussion on the popular “climate sceptic” website Watts Up With That?. I hope it goes without saying to most readers that the rise in methane concentrations since 2007 does not “disprove global warming”. Whilst the recent fluctuations do seem to be driven by changes in natural emissions, it is worth bearing in mind that man-made emissions account for around 60% of the total emission rate (and hence the more than doubling of concentration since pre-industrial times). The continuing rise in concentration of all greenhouse gases is of a great deal of concern (see the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report for a comprehensive review of the latest climate science).