We recently published a paper “Recent and Future Trends in Synthetic Greenhouse Gases” in Geophysical Research Letters describing recent trends in “synthetic” greenhouse gases (gases with no significant natural sources), and their possible impact on climate in the coming decades. The paper was summarised on the American Geophysical Union blog (thanks to Alexandra Branscombe!), and is described in the following University of Bristol press release:

“The total warming impact of 25 major synthetic greenhouse gases has been examined by an international team, led by researchers from the University of Bristol.

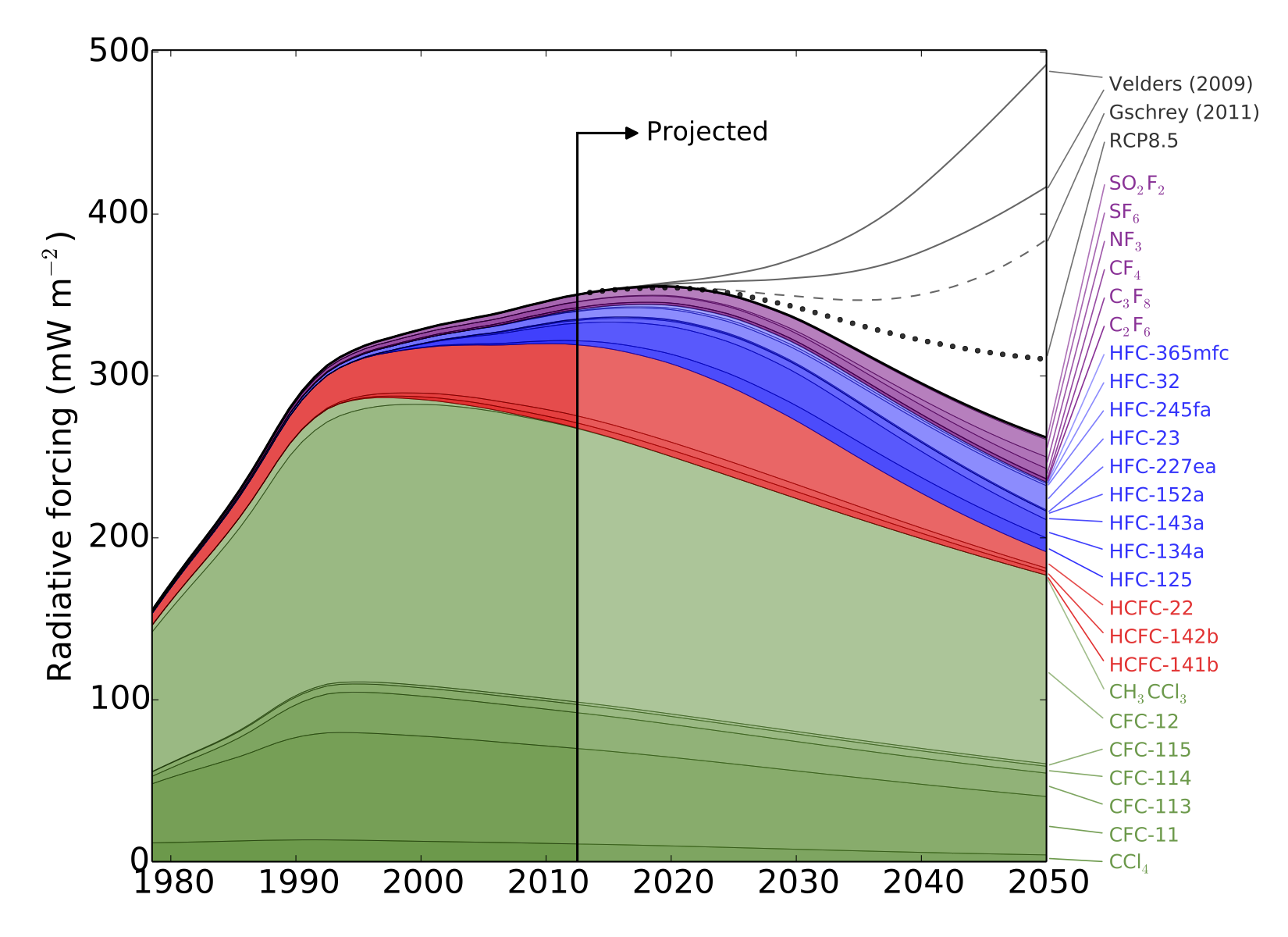

The study estimates that, without additional limits on synthetic greenhouse gas use, the resulting increase in warming could outweigh the climate benefits gained thus far from phasing down chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs).

CFCs—commonly used in refrigerators and air conditioners—garnered public attention for their role in creating a hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica. As these chemicals were phased-down thanks to international agreements limiting their use, they were replaced by other synthesized gases that can still be harmful to the ozone layer and are greenhouse gases that contribute to climate change. Despite this, synthetic greenhouse gases (SGHGs) beyond the CFCs have received relatively little attention from the research community—until now.

The study, led by Dr Matthew Rigby in Bristol’s School of Chemistry, analysed observed atmospheric levels of SGHGs from 1978 to 2012, and then used these measurements to predict the impact these gases could have on global warming through 2050.

In response to the phase-down of CFCs through the 1987 Montreal Protocol, the researchers discovered that the use of other synthetic gases as refrigerants—such as hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs)—has risen. HFCs had been limited in the now-defunct 1997 Kyoto Protocol, but there is currently no agreement restricting their use. So, using HFCs as a test case, the researchers examined the effect of phasing down HFCs by amending the Montreal Protocol to include these gases.

Dr Rigby said: “We could avoid adding the equivalent of up to another three years of carbon dioxide emissions into the atmosphere if these gases were being phased down.”

HFCs are particularly strong greenhouse gases, so even relatively small levels in the atmosphere can contribute to warming.

“Per tonne of emissions, HFCs are much more potent greenhouse gases than carbon dioxide, and are very good at trapping the radiation that heats the Earth,” Dr Rigby said.

While HFCs are currently not a major driver of climate change compared to carbon dioxide or even other SGHGs, the researchers point out that if unabated they may contribute significantly to future warming.

The study used measurements of SGHG levels from the Advanced Global Atmospheric Gases Experiment (AGAGE), a global observing system developed by Professor Ronald Prinn of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and colleagues, and sponsored by NASA and other agencies.

Professor Prinn, co-director of the MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change and a co-author of the report said: “Addressing HFCs, and other SGHGs, now will ensure that they don’t contribute significantly to warming in the future.”

Meanwhile, the researchers note that due to extensive use, CFCs will continue to warm the planet for years to come.

“CFCs have contributed the most among the synthetic greenhouse gases to warming. Their use peaked and levels are now declining, but these gases will remain in the atmosphere for many years. This is likely the trend we will see with most SGHG gases, so it is important that we address these gases now before they do more severe damage,” said Professor Prinn.”

(With particular thanks to Audrey Resutek who wrote the MIT press release that this is based on).