I was recently interviewed for a report on the environmental impacts of refrigerant gases on behalf of a company that makes hydrocarbon refrigerant blends. The report is called “Hydrocarbons: The Quest For A Green Solution To The Changing Future Of Refrigeration And Air-Conditioning” is available on the PriorityCool Refrigerants website.

Little-studied man-made gases have big warming potential

We recently published a paper “Recent and Future Trends in Synthetic Greenhouse Gases” in Geophysical Research Letters describing recent trends in “synthetic” greenhouse gases (gases with no significant natural sources), and their possible impact on climate in the coming decades. The paper was summarised on the American Geophysical Union blog (thanks to Alexandra Branscombe!), and is described in the following University of Bristol press release:

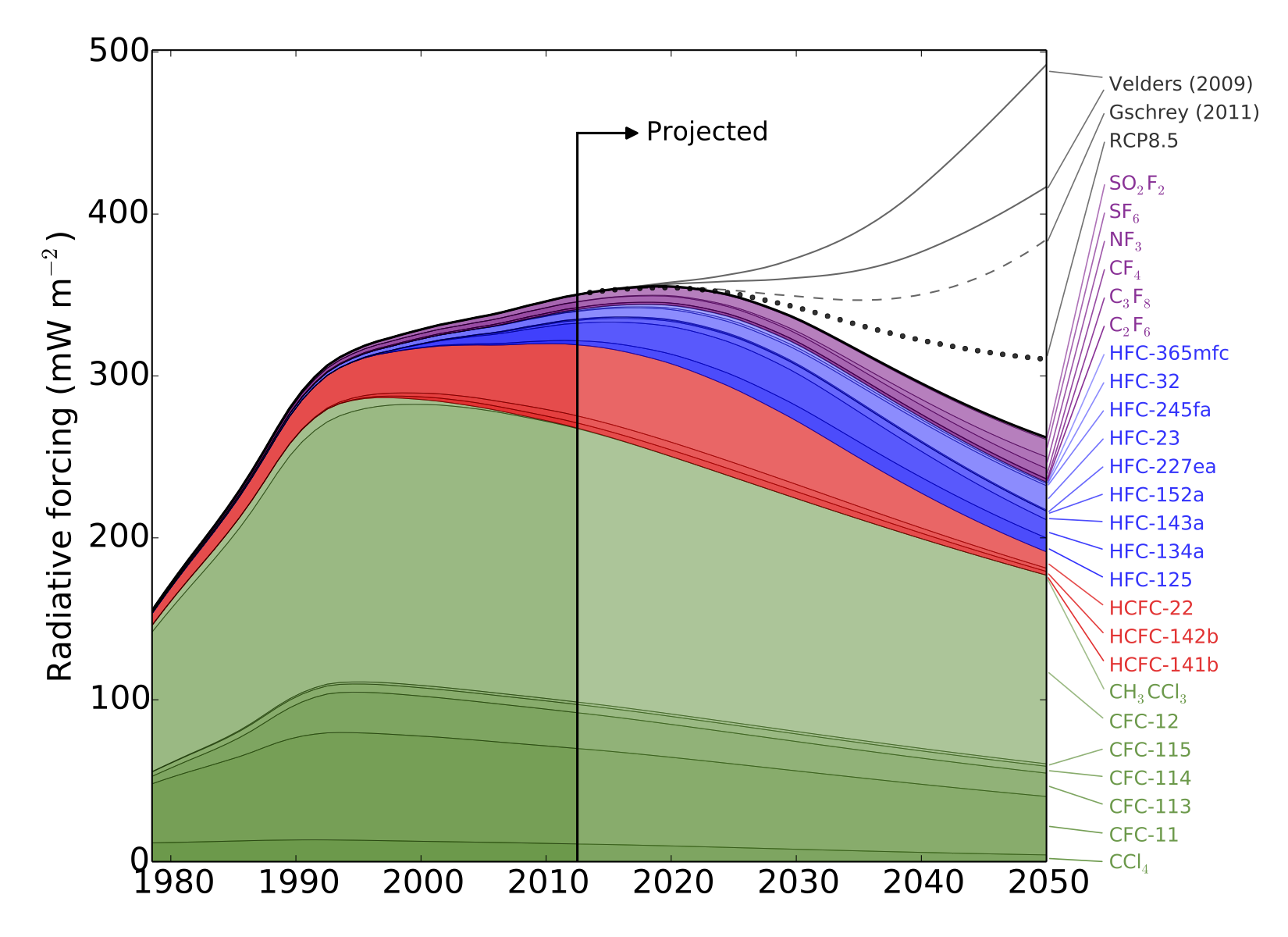

“The total warming impact of 25 major synthetic greenhouse gases has been examined by an international team, led by researchers from the University of Bristol.

The study estimates that, without additional limits on synthetic greenhouse gas use, the resulting increase in warming could outweigh the climate benefits gained thus far from phasing down chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs).

CFCs—commonly used in refrigerators and air conditioners—garnered public attention for their role in creating a hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica. As these chemicals were phased-down thanks to international agreements limiting their use, they were replaced by other synthesized gases that can still be harmful to the ozone layer and are greenhouse gases that contribute to climate change. Despite this, synthetic greenhouse gases (SGHGs) beyond the CFCs have received relatively little attention from the research community—until now.

The study, led by Dr Matthew Rigby in Bristol’s School of Chemistry, analysed observed atmospheric levels of SGHGs from 1978 to 2012, and then used these measurements to predict the impact these gases could have on global warming through 2050.

In response to the phase-down of CFCs through the 1987 Montreal Protocol, the researchers discovered that the use of other synthetic gases as refrigerants—such as hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs)—has risen. HFCs had been limited in the now-defunct 1997 Kyoto Protocol, but there is currently no agreement restricting their use. So, using HFCs as a test case, the researchers examined the effect of phasing down HFCs by amending the Montreal Protocol to include these gases.

Dr Rigby said: “We could avoid adding the equivalent of up to another three years of carbon dioxide emissions into the atmosphere if these gases were being phased down.”

HFCs are particularly strong greenhouse gases, so even relatively small levels in the atmosphere can contribute to warming.

“Per tonne of emissions, HFCs are much more potent greenhouse gases than carbon dioxide, and are very good at trapping the radiation that heats the Earth,” Dr Rigby said.

While HFCs are currently not a major driver of climate change compared to carbon dioxide or even other SGHGs, the researchers point out that if unabated they may contribute significantly to future warming.

The study used measurements of SGHG levels from the Advanced Global Atmospheric Gases Experiment (AGAGE), a global observing system developed by Professor Ronald Prinn of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and colleagues, and sponsored by NASA and other agencies.

Professor Prinn, co-director of the MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change and a co-author of the report said: “Addressing HFCs, and other SGHGs, now will ensure that they don’t contribute significantly to warming in the future.”

Meanwhile, the researchers note that due to extensive use, CFCs will continue to warm the planet for years to come.

“CFCs have contributed the most among the synthetic greenhouse gases to warming. Their use peaked and levels are now declining, but these gases will remain in the atmosphere for many years. This is likely the trend we will see with most SGHG gases, so it is important that we address these gases now before they do more severe damage,” said Professor Prinn.”

(With particular thanks to Audrey Resutek who wrote the MIT press release that this is based on).

GAUGE Barometer podcast

With thanks to Sam Illingworth from the University of Manchester, here’s a little podcast about the modelling activities in GAUGE:

http://thebarometer.podbean.com/2014/01/30/gauge-from-the-model/

35 years of AGAGE measurements

I’ve just returned from the 35th anniversary AGAGE meeting in Boston, MA. I’ve written a blog post for the Cabot Institute, summarising the changes AGAGE has seen during this time:

“I work on an experiment that began when the Bee Gees’ Stayin’ Alive was at the top of the charts. The project is called AGAGE, the Advanced Global Atmospheric Gases Experiment, and I’m here in Boston, Massachusetts celebrating its 35-year anniversary. AGAGE began life in 1978 as the Atmospheric Lifetimes Experiment, ALE, and has been making high-frequency, high-precision measurements of atmospheric trace gases ever since.

At the time of its inception, the world had suddenly become aware of the potential dangers associated with CFCs (chlorofluorocarbons). What were previously thought to be harmless refrigerants and aerosol propellants were found to have a damaging influence on stratospheric ozone, which protects us from harmful ultraviolet radiation. The discovery of this ozone-depletion process was made by Mario Molina and F. Sherwood Rowland, for which they, and Paul Crutzen, won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1995. However, Molina and Rowland were not sure how long CFCs would persist in the atmosphere, and so ALE, under the leadership of Prof. Ron Prinn (MIT) and collaborators around the world, was devised to test whether we’d be burdened with CFCs in our atmosphere for years, decades or centuries.

ALE monitored the concentration of CFCs, and other ozone depleting substances, at five sites chosen for their relatively “unpolluted” air (including the west coast of Ireland station which is now run by Prof. Simon O’Doherty here at the University of Bristol). The idea was that if we could measure the increasing concentration of these gases in the air, then, when combined with estimates of the global emission rate, we would be able to determine how rapidly natural processes in the atmosphere were removing them.

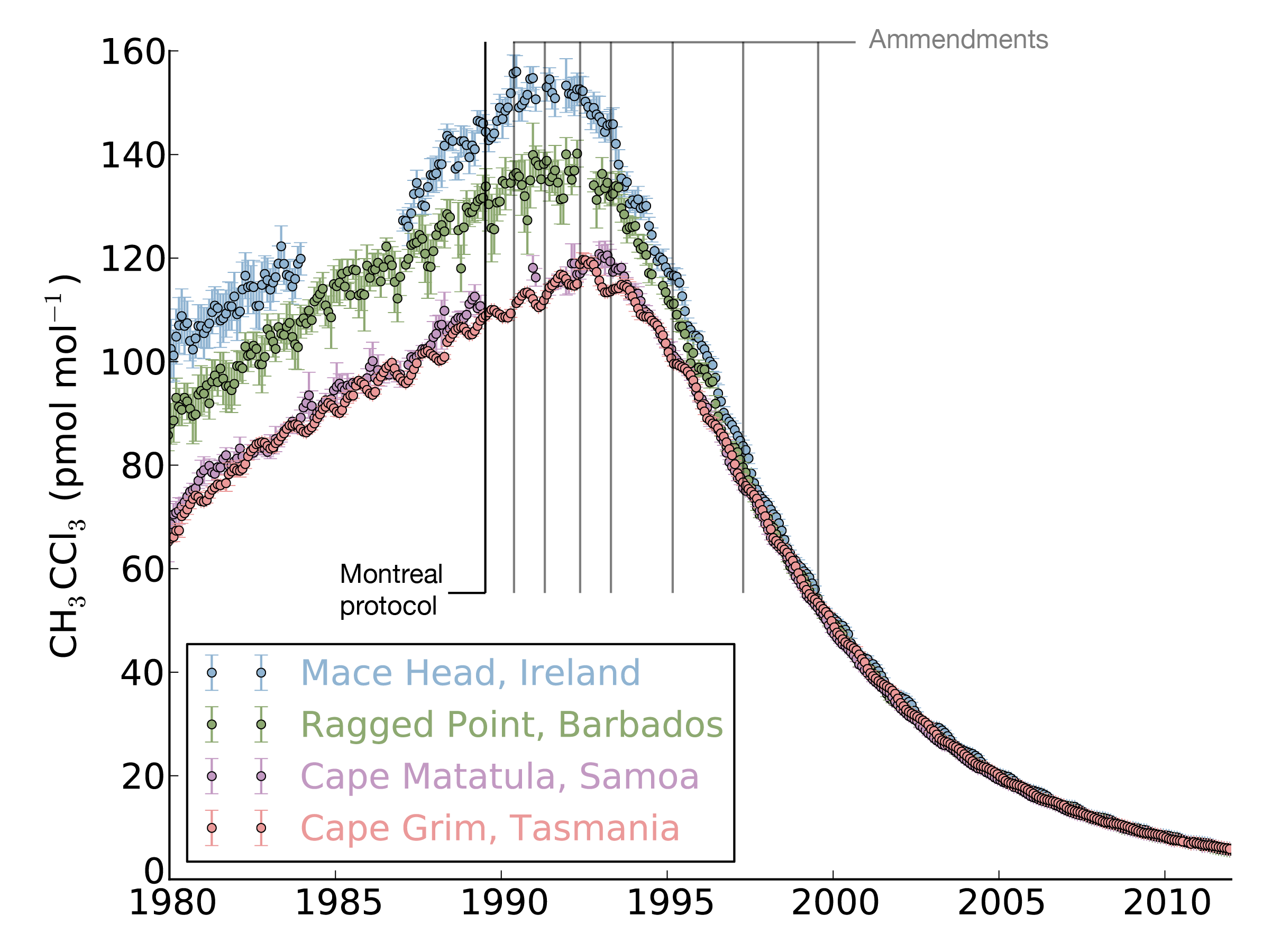

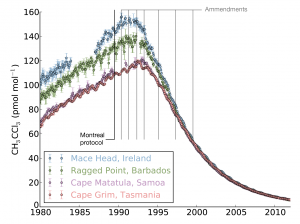

Thanks in part to these measurements, we now know that CFCs will only be removed from the atmosphere over tens to hundreds of years, meaning that the recovery of stratospheric ozone and the famous ozone “hole” will take several generations. However, over the years, ALE, and now AGAGE, have identified a more positive story relating to atmospheric CFCs: the effectiveness of international agreements to limit gas emissions.

The Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer was agreed upon after the problems associated with CFCs were recognised. It was agreed that CFC use would be phased-out in developed countries first, and developing countries after a delay of a few years. The effects were seen very rapidly. For some of the shorter-lived compounds, such as methyl chloroform (shown in the figure), AGAGE measurements show that global concentrations began to drop within 5 years of the 1987 ratification of the Protocol.

Over time, the focus of AGAGE has shifted. As the most severe consequences of stratospheric ozone depletion look like they’ve been avoided, we’re now more acutely aware of the impact of “greenhouse” gases on the Earth’s climate. In response, AGAGE has developed new techniques that can measure over 40 compounds that are warming the surface of the planet. These measurements are showing some remarkable things, such as the rapid growth of HFCs, which are replacements for CFCs that have an unfortunate global-warming side effect, or the strange fluctuations in atmospheric methane concentrations, which looked like they’d plateaued in 1999, but are now growing rapidly again.

The meeting of AGAGE team members this year has been a reminder of how important this type of meticulous long-term monitoring is. It’s also a great example of international scientific collaboration, with representatives attending from the USA, UK, South Korea, Australia, Switzerland, Norway and Italy. Without the remarkable record that these scientists have compiled, we’d be much less well informed about the changing composition of the atmosphere, more unsure about the lifetimes of CFCs and other ozone depleting substances, and unclear as to the exact concentrations and emissions rates of some potent greenhouse gases. I’m looking forward to the insights we’ll gain from the next 35 years of AGAGE measurements!”

GAUGE kicks off!

On the 1st March, we officially began our new £3m NERC-funded consortium project Greenhouse gAs Uk and Global Emissions (GAUGE). The University of Bristol press release explains:

Scientists awarded grant to determine UK’s greenhouse gas emissions

Press release issued 1 March 2013

Researchers in the University of Bristol’s Atmospheric Chemistry Research Group (ACRG), in collaboration with scientists around the country, have been awarded funding from the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) to provide an independent ‘top-down’ check on the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions estimates.

The UK is required to estimate how much climate-warming carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide it emits each year. However, at the moment, these estimates rely heavily on so-called ‘bottom-up’ accounting methods that may be subject to biases and inaccuracies.

The GAUGE project (Greenhouse gAs Uk and Global Emissions) is a three and a half year collaboration between several universities and research institutions across the UK.

ACRG’s Professor Simon O’Doherty, who also runs the UK greenhouse gas monitoring network funded by the Department for Energy and Climate Change, said: “It’s important that we expand our greenhouse gas observation capabilities in this country, if we’re really going to understand what we’re emitting. But it’s equally important that we begin exploring new types of measurement, which may help us understand emissions processes more fundamentally.”

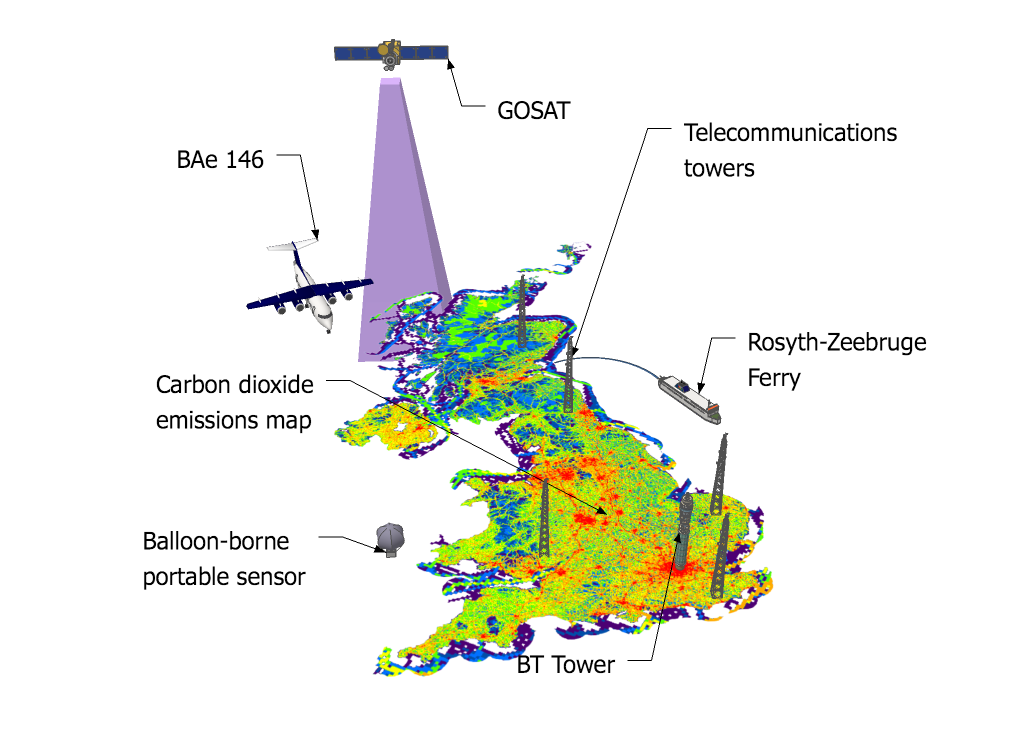

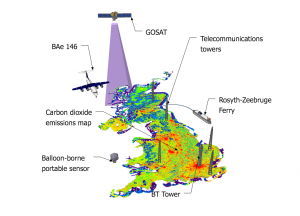

GAUGE will bring together a more comprehensive suite of greenhouse gas observations around the UK than has ever been compiled. The project will determine emissions using information from satellites, aircraft, tall towers (including the BT tower in the middle of London), balloons and boats.

In addition to developing new measurements, GAUGE will use computer models to simulate how greenhouse gases travel through the air.

Dr Matt Rigby, a research fellow at ACRG, said: “By measuring the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, and then using computer models to simulate where the air came from in the days before the measurements, we can determine emissions from the surrounding areas. This new funding will allow us to develop these methods with the help of the Met Office and GAUGE partners at other universities.”

Using the new measurements and modelling techniques, GAUGE researchers hope to make the UK’s emissions amongst the best-quantified in the world.

Using new measurement technology to estimate methane sources

Although methane is the second most important greenhouse gas its sources are quite poorly understood. However, new methods of measuring atmospheric methane may be able to help.

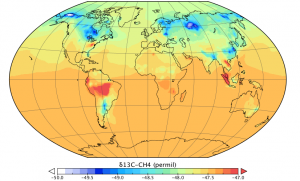

Methane is a molecule containing one carbon and four hydrogen atoms. These atoms usually have an atomic mass unit of 12 (carbon) and 1 (hydrogen). However, they also occur in higher masses in nature, called isotopes. Carbon-13 and deuterium (hydrogen with a mass of 2) occur in one atom for every few thousand atoms of regular carbon or hydrogen. This becomes potentially useful for us, because different sources of methane emit molecules with slightly different ratios of carbon-12 to carbon-13 or different ratios of hydrogen to deuterium. For example, methane emitted from wetlands has less 13C than the average in the atmosphere, whereas wildfires emit methane with a relatively high deuterium content.

So, by measuring methane concentrations and isotope ratios in the atmosphere, we can hope to learn something more about where the methane came from.

In the last few years, advances in laser spectroscopy have meant that we can now measure the isotopic composition of methane by shining lasers through a sample and measuring the absorption of certain wavelengths. However, the variations in methane isotope ratio that we expect to see in the atmosphere are very small. Therefore, to be able to resolve small changes, some people are proposing to also “pre-concentrate” air samples, which means that we remove a lot of the nitrogen, oxygen and other major components of air, to leave a more concentrated sample of methane that can be analyzed. Similar systems exist for measuring concentrations of other gases, but not yet for methane isotopes.

In this paper, we asked the question: “If we had these instruments at each AGAGE station, how much better would we be able to constrain methane emissions from different sources than we can at present?”. The answer we found was a little mixed. We found that these new measurements would provide additional information about the methane emissions to the atmosphere. However, the amount by which the uncertainties in our current estimates of methane emissions would be reduced is a little smaller than we hoped for. For example, for wetlands (the single largest source) and other microbial sources, we found that global uncertainty reduction would be reduced by only around 3%. For smaller sources that had a more “distinct” source isotope ratio such as biomass burning, larger relative uncertainty reductions were possible (9%).

Despite the relatively modest uncertainty reductions, my feeling is that, given the importance of methane in the global climate system, these new instruments will have a role to play in a future methane observing system. Given the complexity of the system, no single measurement (or modeling) strategy will be able to fully determine the causes of the strange changes we see in methane. However, by combining many measurement types, we should be able to understand the system better than we currently do.

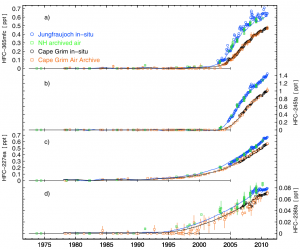

Four new HFCs

Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) are replacements for chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), whose use is being phased out because they are primarily responsible for depleting the ozone layer. While HFCs don’t destroy ozone, they are often very powerful greenhouse gases, so it is important that we monitor their concentration and emissions. One difficulty in doing this is that there are many HFCs emitted into the atmosphere, and new ones are appearing all the time.

To keep track of these gases, my colleagues in the AGAGE network have developed a system that can measure gas concentrations using mass spectrometry. The system is able to detect gases at very low concentrations, by removing most of the nitrogen and oxygen from the measured samples, increasing the concentration of the pollutants they want to measure. This means that we can now detect ‘new’ gases very soon after they appear in the atmosphere.

In this paper, Martin Vollmer from Empa in Switzerland describes the measurement of four HFCs that have appeared in the atmosphere over he last decade or so (HFC-227ea, HFC-236fa, HFC-245fa, HFC-365mfc). Using a combination of in situ measurements, and new measurements of archived air samples, we can determine the entire air history of the four gases, from the year they first appeared in detectable amounts.

Using these observations, and a two-dimensional model of the atmosphere, we calculated the annual global emission rates. As is often the case, the emissions we found differed from inventory estimates by substantial amounts, highlighting the value of these sort of ‘top-down’ verification techniques.

Museum of Science Podcast

A group of us from the MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change were interviewed for a Boston Museum of Science podcast that came out on Friday. The main focus of the podcast was on how 2010 being the warmest year on record links with our work. You can find it here.